The news that Jayant Chaudhary’s Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD), the Jat party in Uttar Pradesh, may be leaving the I.N.D.I. Alliance and reuniting with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), came just as the week was getting underway and the excitement surrounding India’s test victory at Vizag had not yet subsided.

An alliance between the RLD and BJP will make it difficult for the opposition to gain even a small number of seats in the state, which is a serious blow to the opposition unity and the Congress party, as well as its senior coalition partner in Uttar Pradesh, the Samajwadi Party (SP).

As it stands, following the Bahujan Samaj Party’s (BSP) announcement that it would be running independently in the general elections of 2024, the opposition unity score fell precipitously. However, the RLD’s change has further reduced the chances of the opposition.

Furthermore, given that this action follows the sudden but predictable exit of Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar from the opposition ranks last month and the announcement by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee that her party would be running for every seat in her state, the upshot is that the Congress-led coalition is doomed in the north.

The clear implication is that another sweep of the Indo-Gangetic plains is anticipated for the BJP and its allies. Is this move limited to just that, though? Or is there another, more comprehensive angle that would allow for a deeper appreciation? Indeed, there is.

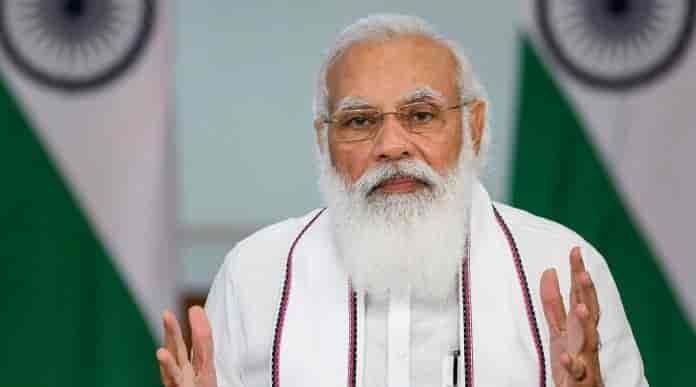

The RLD’s decision to join the BJP instead of the Congress is only symbolic of a bigger political plot. To put it plainly, this is Amit Shah and Narendra Modi organizing an insurance poll in 2024 to safeguard their party’s chances in the 2029 elections in the event that the BJP undergoes a leadership transition.

We say this because there’s precedent: he did exactly similar in Gujarat in the run-up to the assembly elections in 2012, setting the stage for his move to Delhi.

Examine the similarities:

During a contentious campaign in 2007, Modi had to endure a lot of insults. He was referred to as a “merchant of death” or “maut ka saudagar” by Congress President Sonia Gandhi. During this period, Modi and the BJP in Gujarat were under intense scrutiny from central agencies.

Despite this, Modi guided the BJP to a resounding win. After securing the mandate, he proceeded to reduce the size of the state’s Congress. Using every tactic in the book, state officials, district barons, and the general populace of the Congress cadre were either neutralized, co-opted, or sidelined and rendered ineffectual.

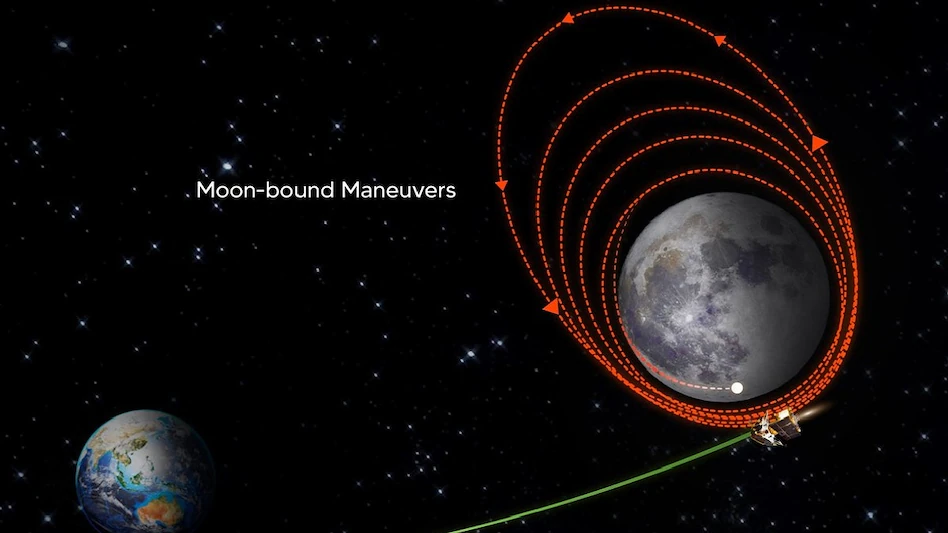

It was a methodical, elegant, and silent process. Only as the 2012 assembly elections drew nearer, and Congress leader after Congress leader proved unable to muster the strength to halt the Modi juggernaut, did the results begin to emerge. Modi had set the stage for BJP wins in areas where it had not historically performed well, like as the tribal belt, and by the time the party’s central leadership realized what had happened, it was too late.

In order to prevent too much damage to the BJP’s Gujarati voter base upon Modi’s move to Delhi, this was Modi’s first insurance election. The point was demonstrated during the 2017 assembly elections when the Congress attempted to derail the BJP by using not one, not two, but three flagrant and divisive caste cards.

In 2017, the BJP emerged victorious, but not before going through a few restless nights, some upsets, and a warning from the voters that the hole left by Modi needed to be filled with more determination.

Let’s now examine the context of the 2019 general elections in order to make comparisons. It was every bit as divisive as the Gujarat Assembly elections of 2012.

The revolting catchphrase of the Congress party was “chowkidar chor hai.” And if their attempts in 2007 had been to show that Modi was criminally responsible for the riots of 2002, then in 2019 they tried to use the Rafale jet fighter purchase to place a comparable blame on Modi.

Naturally, it was a bust. The Supreme Court made Rahul Gandhi apologize, and the BJP was given a larger mandate. Since then, Modi has worked to replicate what he did to the Congress in Gujarat between 2007 and 2012 on a national scale.

The public views the top leadership of the Congress as nothing more than a farce. Across other states, their cadres have nearly vanished. Their painstakingly constructed coalitions are in ruins. This is the reason we suggest that the possible RLD-BJP alliance is only a minor portion of the bigger picture.

It is irrelevant that the Congress has been completely unable to stop the BJP from winning a third straight mandate. The real point is that, just as he did in 2012, Modi has once again prepared the ground for an insurance election in 2024 to guarantee his party’s prospects of survival in the event of a leadership shift by 2029.

A political party should operate as follows: it should plan, groom the next generation of leaders, consolidate its support in strongholds, extend into weaker areas, form alliances, and counter new political threats as they arise. This is how a political party should operate. And thus lies the distinction between the Congress and the BJP.

With a well-managed insurance poll, Modi is already paving the way for the next generation of leaders, while the Congress continues to play musical chairs with its first family and its courtiers.