Concerns have been expressed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) over India’s debt’s long-term viability. It issued a warning that, in the near future, general government debt is probably going to surpass 100% of India’s GDP, according to Business Standard. Another area of emphasis was the necessity of making large investments to meet climate change targets.

Because significant investment is needed to meet India’s climate change mitigation commitments and increase the country’s resilience to climatic pressures and natural disasters, long-term risks are substantial. According to the IMF’s annual Article IV consultation report, “this suggests that new and preferably concessional sources of financing are needed, along with greater private sector investment and carbon pricing or equivalent mechanism.”

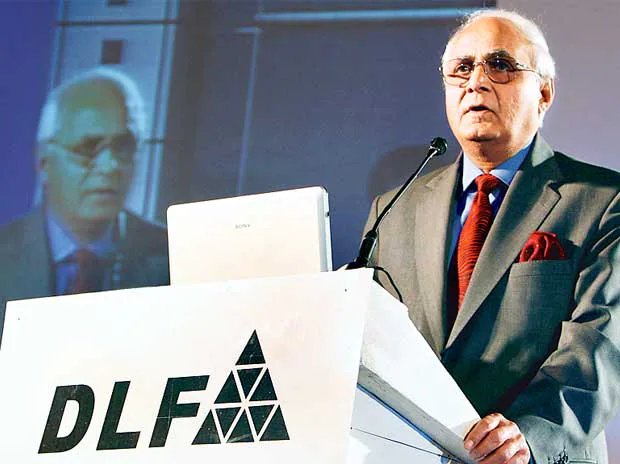

The Indian government, however, has refuted these alerts, claiming that because its debt is primarily denominated in local currency, the dangers connected with sovereign debt are significantly reduced. In the same study, India’s executive director at the IMF, KV Subramanian, expressed dissatisfaction with the IMF’s estimates, citing previous shocks that India has experienced and highlighting the gradual increase in the public debt-to-GDP ratio.

“The staff prognosis that debt sustainability risks are high in the long run can also be said to be true,” he stated. Because government debt is mostly issued in native currency, the risks associated with it are relatively low. India’s public debt-to-GDP ratio at the general government level has barely climbed from 81 percent in 2005–06 to 84 percent in 2021–22 and back to 81 percent in 2022–23, despite the numerous shocks the world economy has experienced over the last 20 years.”

Various Opinions Regarding Exchange Rate

Additionally, the Indian currency rate regime was reclassified by the IMF from “floating” to “stabilized arrangement.” The Indian side opposed this adjustment, calling it “unjustified” and predicated on “subjective selection.”

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) vehemently disagreed, arguing that their actions were required to reduce excessive volatility, despite the IMF raising worries about how foreign exchange intervention (FXI) could affect the rupee-USD exchange rate. Additionally, Subramanian refuted the IMF’s portrayal, highlighting the ongoing significance of exchange rate flexibility in mitigating outside shocks.

The domestic pressures in India are not understood by the IMF. The central bank must aggressively control the volatility of the rupee as import inflation, which affects 1.4 billion people, is a significant component of India’s overall inflation, a government official told the newspaper.

Growth Prospects and Controlling Inflation

The IMF recognized India’s successful use of large-scale government measures to control inflation during increases in the price of commodities globally. The report presents a balanced prognosis for India’s economic growth, noting an increase in the potential growth rate over the medium term, from the previously expected 6 percent to 6.3 percent. The Indian government, on the other hand, was more upbeat, projecting a possible growth rate of 7-8 percent.

Rather of significant government action, Subramanian credited India’s lower inflation rate during the pandemic to a distinctive economic policy. He highlighted India’s careful balancing act between supply-side and demand-side policies.

Subramanian denied the idea that there are any enduring vulnerabilities in non-banking financial businesses (NBFCs), in contrast to the IMF’s worries about such issues. He emphasized the solid macroeconomic foundations and forecast a growing investor base due to the impending addition of emerging government bond indices.

“Given the solid economic fundamentals, staff’s hypothesis that a sharp rise in sovereign risk premia may strain balance sheets and bank lending appetite seems implausible. The upcoming inclusion in emerging government bond indices will diversify risks and increase the pool of potential investors,” he continued.