Starting on July 1, three new criminal laws will take the place of the British-era IPC, CrPC, and Evidence Act. Digitization, harsher punishments, and electronic FIRs are among the modifications.

As per the announcement made by the Center, the three new criminal laws, namely Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and Bharatiya Saksha Adhiniyam (BSA), will take effect on July 1st, 2018. These laws aim to replace the Indian Penal Code (IPC) of the British era, the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), and the Indian Evidence Act.

Three different notices were sent out by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) late on Friday night informing people of the new rules. The notification for BNS stated, “The Central Government hereby appoints the 1st day of July 2024 as the date on which the provisions of the said Sanhita, except the provision of sub-section (2) of section 106, shall come into force, in exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (2) of section 1 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (45 of 2023).” Notifications for BNSS and BSA were identical.

Following resistance from truckers, the first-ever introduction of sub-section (2) of Section 106 of BNS—which addresses “hit-and-run” incidents—was placed on hold. They began a three-day nationwide protest in January to voice opposition to the provision, which calls for a 10-year jail sentence and a fine of ₹7 lakh in cases of hit-and-run heavy transport vehicles. This punishment is comparable to that given in a murder conviction. The All-India Motor Transport Congress was informed at the time by the MHA that this clause would only be enacted following more consultations.

The new laws were presented in Parliament on August 11 and referred to a parliamentary standing committee under the direction of Home Minister Amit Shah. On December 12, a group of new legislation (designated as the second) were introduced in the Lower House, taking into account some of the panel’s recommendations. The laws were approved by both Houses at the same time that 46 members of the Rajya Sabha and 97 members of the Opposition were suspended from the Lok Sabha for misbehaving, a measure that had never before been taken during a winter session. (VERIFY)

A few of the most significant modifications address offenses of terrorism and crimes against the state, permit electronic first information reports to be registered, account for electoral process manipulation, and designate electronic evidence as primary proof. For the first time, specific definitions of crimes have been established, including lynching, along with more stringent penalties for offenses against women and children.

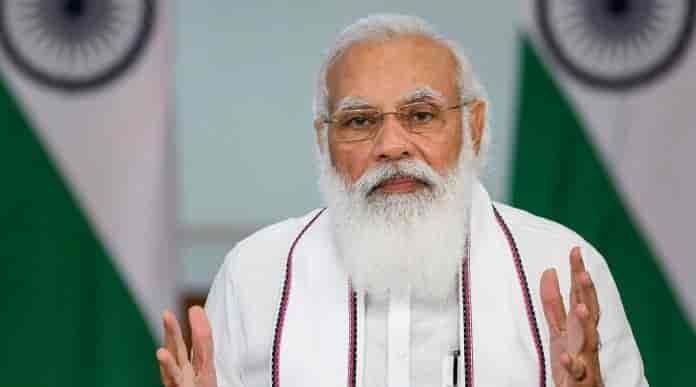

“The objective of the IPC was to punish and not deliver justice. All the three laws, which are over 150 years old, were made by the British to rule over us,” Shah said in Lok Sabha on December 20. “Prime Minister Narendra Modi decided to remove all such remnants of the colonial era.”

All told, 313 amendments have been made to the laws, which, according to Shah, will significantly alter India’s criminal justice system and enable every citizen to obtain justice in no more than three years. Whereas the IPC had 511 sections, the BNS, which takes its place, had 356 sections. Eight new sections have been created, and 22 sections have been abolished in the BNS, while 175 parts have been changed.

Now with 533 sections, BNSS takes the position of CrPC. Nine new sections were added, and the number of repealed sections was equal to the number of altered sections (160). The Indian Evidence Act will be replaced by the BSA, which will include 170 sections as opposed to the previous 167.

The new regulations stipulate that information about victims will be delivered digitally and that documents, such as charge sheets, zero-FIRs, and e-FIRs, shall be generated and supplied electronically. A significant clause that outlines the qualifications, duties, and authority of the several authorities within the Directorate of Prosecution was introduced to the new statutes. To guarantee coordination, the roles and responsibilities of the several tiers of prosecuting officials have been defined. During the investigation stage, prosecutors are now able to provide monitoring.

“The new codes were enacted with the purest of intentions. The intention was to draft legislation that would reflect the needs of Indian society and the times, according to Prakash Singh, the former director general of police in Uttar Pradesh, who made this statement on Saturday. “But I think the entire exercise was done a bit too quickly.”

“I don’t know if we have demonstrated the same thoroughness as the British, but their laws have served the nation well over the years. I think there would be implementation hiccups for a few years because society and the police were accustomed to specific legal phrases. The training of thousands of police officers comes next, and that will take time, he continued. “I wish more consultation had taken place.”

Within a year, all police stations nationwide will begin putting the laws into practice, according to a statement made by the home ministry last month. First, union territories like Chandigarh and Delhi would be subject to the legislation.

Commissioner of Delhi Police Sanjay Arora stated, “We are holding a lot of training sessions for our officers and will be ready for implementation of the new laws by July 1.”

A one-, three-, and five-day course, information flyers, and study materials have been developed by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) and the Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPRD) to help law enforcement agencies nationwide quickly become familiar with the provisions of the new laws, which heavily rely on technology and forensics. In order to comply with the reforms, police agencies are being required to improve their forensic capabilities and modify their systems.

In addition, the home ministry is purchasing 900 forensic labs and supplying police departments with 3,000 trainers who will instruct officers even more. Officials acquainted with the developments stated on condition of anonymity that Chandigarh and Delhi police had arranged several training sessions for police officers to become conversant with the new regulations.

Shah had asked the police chiefs to train officers from SHO rank to DGP level and upgrade the technology from police station to police headquarters for the successful implementation of the three criminal laws in January, during his speech at the annual director generals of police conference in Jaipur.

“The three criminal major Acts were implemented more than hundred years ago and were in dire need of modifications. As a criminal lawyer, I have always felt that the procedure of trials, the definitions of the penal offences and the law of evidence are archaic,” said senior advocate Vikas Pahwa. “They need radical changes and have to be in sync with modern India. Any law formulated on these lines would be propitious for the criminal justice system of our country.”

Pahwa remarked, “I applaud the government’s initiative to introduce these laws.” “The bills will bring about a fundamental improvement in the way trials are conducted in the nation if they pass the litmus test of our pressing judicial needs.”